- Per My Last Thought

- Posts

- The Return of the Feudal Economy

The Return of the Feudal Economy

Feudalism was supposed to be history. Kings, lords, and peasants bound to land they didn’t own. Yet the structure feels familiar again: homes priced out of reach, wealth drifting upward, and a shrinking middle class left paying rent to the few who hold the assets.

Somewhere in the high school history curriculum, we were taught that feudalism was a relic. It was a medieval system of kings, lords, and peasants who worked land they did not own. Then came capitalism, industrial revolutions, and the promise that if you worked hard enough, you could move up. Homeownership was attainable. Wealth was, at least in theory, more evenly distributed.

Yet it feels like the old order has quietly returned. The titles have changed, hedge fund instead of lord, private equity instead of baron, but the structure is starting to look familiar.

When a House Was Affordable

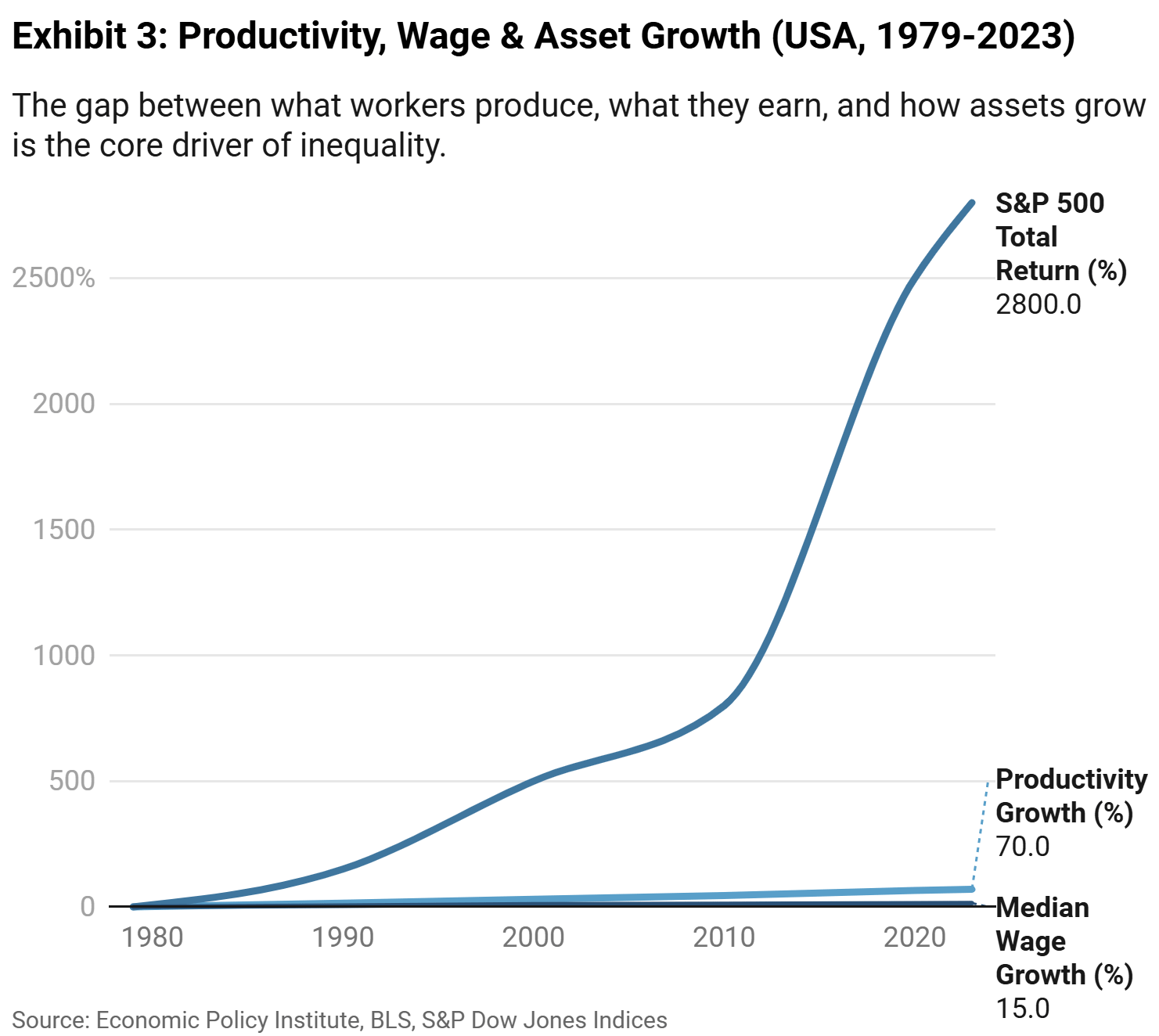

In medieval Europe, wealth meant land. Today, wealth means assets: real estate, equities, private investments. All have inflated far faster than wages.

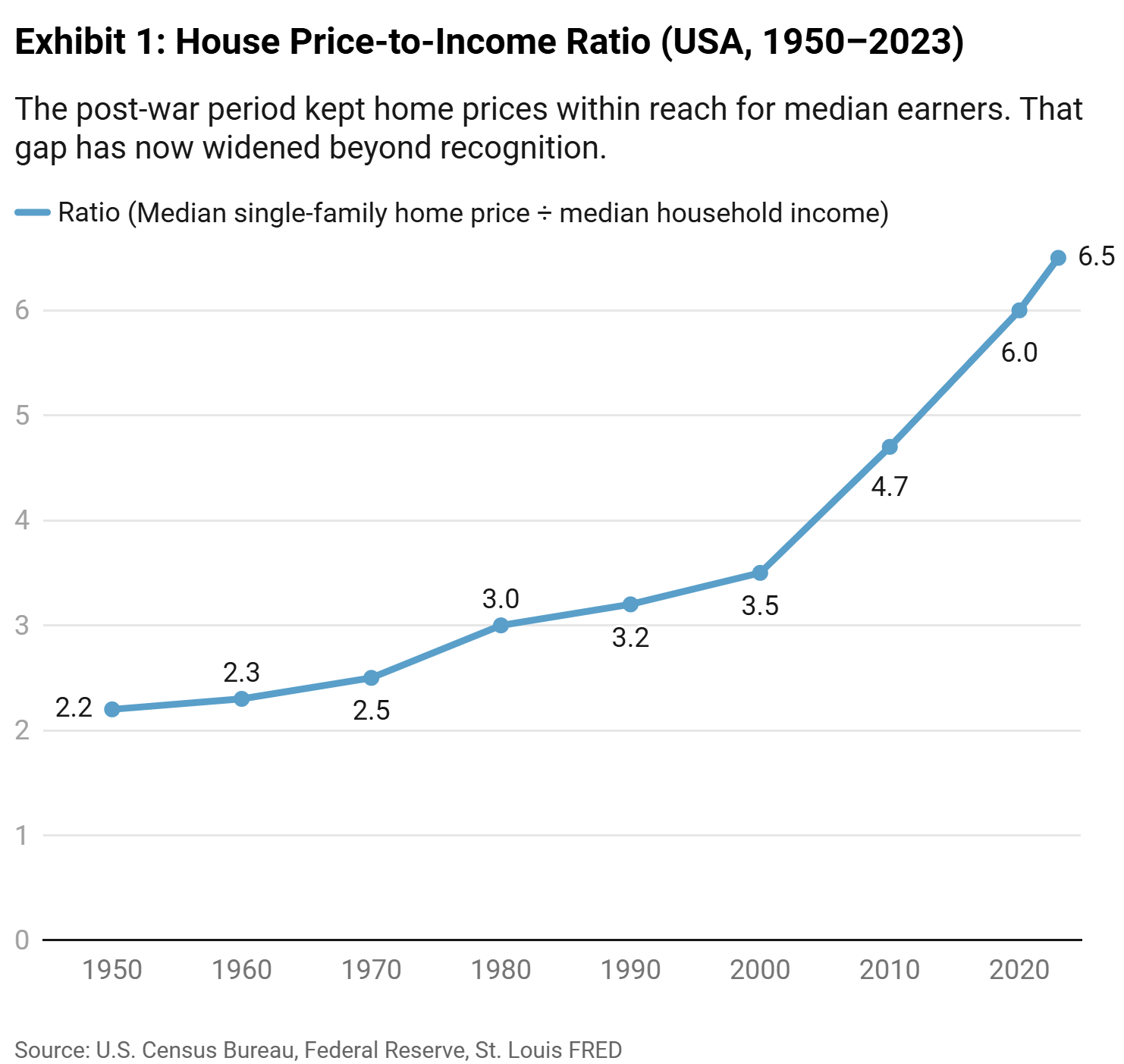

After the Second World War, the average U.S. home cost roughly 2.2 times the median household income. Even into the 1970s, the ratio hovered between 2.5 and 3. Mortgage rates in those decades often sat between 7 and 10 percent, which sounds harsh by modern standards. Yet the principal cost of a house was low enough that ownership was still within reach. A single-income household could secure a mortgage and expect to pay it off in under 20 years.

Today, the ratio is above 6 nationally and over 10 in cities like San Francisco, London, and Sydney. Mortgage rates may be lower than the double-digit spikes of the 1980s, but paired with record-high principal costs they have pushed ownership out of reach for most. Homes are increasingly accessible only to those with significant capital, institutional investors or inheritance, not wages.

And here lies a key dynamic, as economist Thomas Piketty observed, “when the rate of return on capital exceeds the rate of growth of output and income, wealth concentrates.” That is exactly what housing has become. The rise in home values has outpaced income growth for decades, turning property into a capital asset first and a home second.

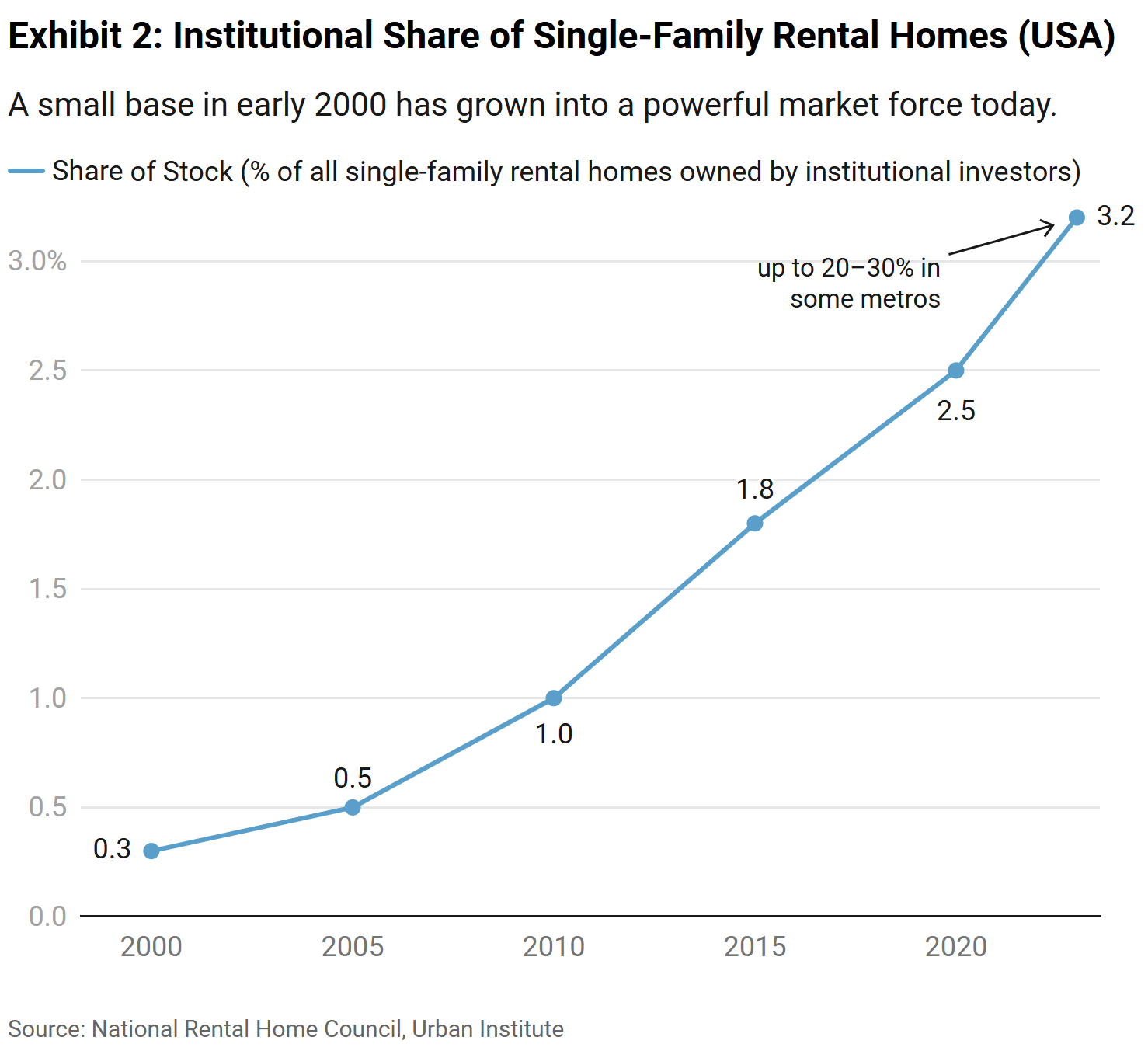

The trend accelerated after the 2008 financial crisis. In the era of near-zero interest rates, loans were cheap for anyone who already had collateral. Institutional investors could borrow billions at almost no cost, scoop up homes, and turn them into rental portfolios. For ordinary households without that starting capital, the same era was not an opportunity. It was the beginning of being permanently priced out.

The Bidder You Can Not Outbid

In the Middle Ages, if you wanted land, you pledged loyalty to a lord. Today, if you want a house, you compete against a cash offer from a fund with a ten-billion-dollar war chest.

Institutional homebuying is no longer rare. In 2000, institutional investors owned about 0.3 percent of U.S. single-family rental homes. By 2023, that share had risen to over 3 percent nationally, with markets like Atlanta and Phoenix seeing 20 to 30 percent of recent home sales go to institutional buyers. They can outbid you without a mortgage, waive inspections, and move faster than any ordinary buyer.

Growth Without Gain

Between 1979 and today, U.S. worker productivity has grown by nearly 70 percent, while inflation-adjusted median wages have risen only 15 percent. Over the same period, the S&P 500’s total return has climbed more than 2,800 percent. Those who owned assets became far wealthier. Those who relied on wages stood still or fell behind, especially once the rising cost of housing, healthcare, and education is factored in.

The result is an economy where ownership is concentrated and renting is the default for most. Whether it is a home, a car, or even software, you are paying to use what someone else owns.

The Hollowing of the Middle

A strong middle class once acted as a buffer between wealth and poverty and was a foundation for stability. In 1971, the middle-income group made up 61 percent of U.S. adults. By 2021, that number had fallen to 50 percent, according to Pew Research. Similar trends appear in the UK, Canada, and Australia.

When the middle class weakens, polarization follows. A small group of asset-owning elites sits at the top, while a large group of wage earners remains dependent on them. History is clear on the consequences of extreme inequality, from social unrest to political breakdown. The details change, but the pattern repeats.

Per My Last Thought - The Next Lords Won’t Own Land

Feudalism ended not because rulers had a change of heart, but because economic systems shifted and productivity gains changed the balance of power. That could happen again, through policy reform, technological disruption, or shifts in capital flows. For now, the trend is moving in the opposite direction.

The next lock on ownership may not be physical at all. As artificial intelligence becomes more capable, the spoils will concentrate in a handful of firms that own the models, the data, and the infrastructure. Your productivity, creativity, and even the tools you depend on could be mediated by a few corporate gatekeepers who have monopolized humanity’s collective knowledge. The outputs may feel personal, but the platforms will be singular.

One can call this technological monopoly. Not in the medieval sense of castles and knights, but as a centralized, all-encompassing order where value creation flows upward to a narrow owner class while everyone else is reduced to digital tenant farmers. This time the lords will not just own the land. They will own the very brain of the economy - a futuristic version of neo-feudalism.

Will governments confront this with policies that check monopolies and protect the commons? Will nations cooperate to manage AI as shared infrastructure, or will they weaponize it in competition? I don’t think I’ve ever had more questions about the future than I do today.