- Per My Last Thought

- Posts

- Kuwait & KSA: A Shared History Few Know About

Kuwait & KSA: A Shared History Few Know About

The Gulf countries share history, sure. But I hadn’t realized how deep the ties between Kuwait and Saudi Arabia ran. Long before borders, pipelines, or summits, there was exile, conflict, and the kind of trust that quietly shaped what came next.

I’ve been reading Kuwait and Her Neighbours by H. R. P. Dickson for over a year now, on and off. It’s a heavy book in every sense. First recommended to me by a Kuwaiti friend, it’s dense, detailed, and full of stories only someone who lived the time could tell.

First, a bit about the author. Dickson became the British Political Agent in Kuwait in 1929. But he wasn’t just another colonial administrator. He and his wife, Violet, spent most of their lives in Kuwait. He spoke fluent Arabic, built close ties with the Al-Sabah family, and immersed himself in Bedouin and tribal culture. Violet became just as rooted, known affectionately to Kuwaitis as Umm Saud.

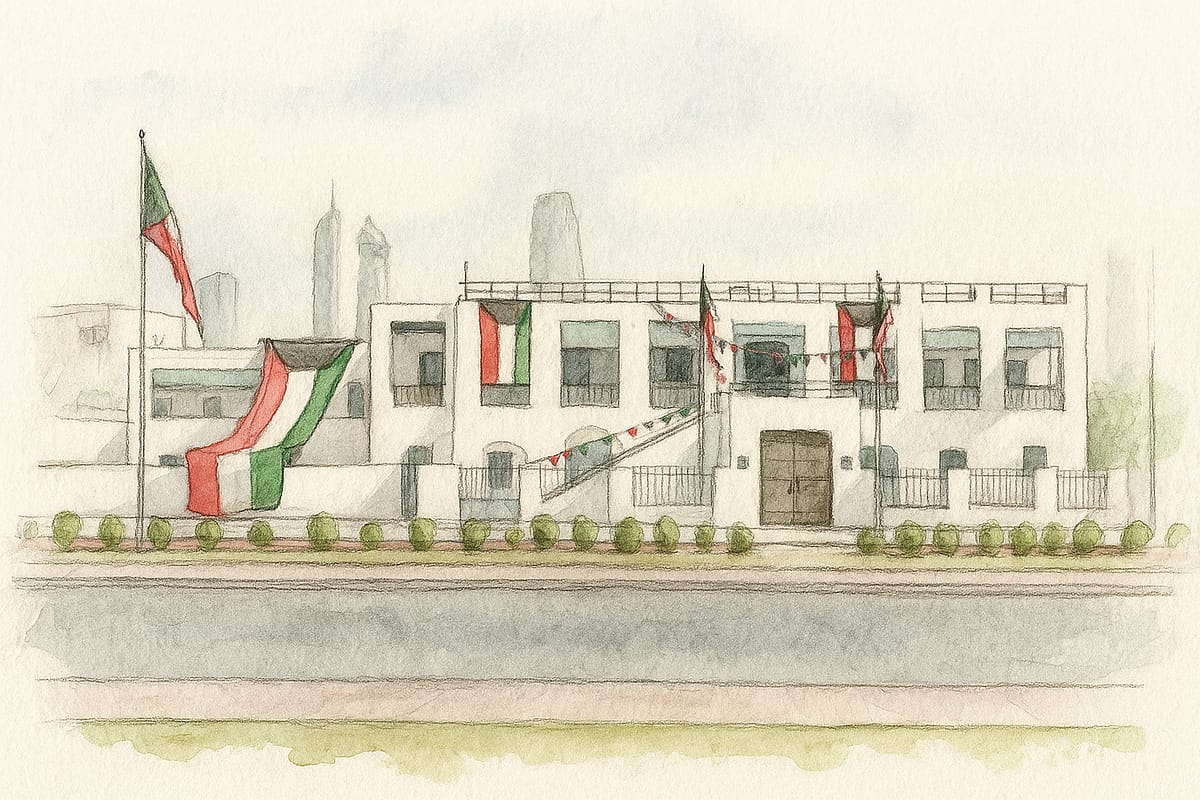

Dickson lived and died in Kuwait. He passed away in 1959 and is buried there. Violet remained until 1990, evacuated during the Iraqi invasion at the age of 94. She died the following year but never stopped calling Kuwait her true home. Their modest two-storey house near the old port still stands today. It’s now the Dickson House, a small museum that quietly preserves the life they lived.

Watercolor illustration of the historic Dickson House in Kuwait

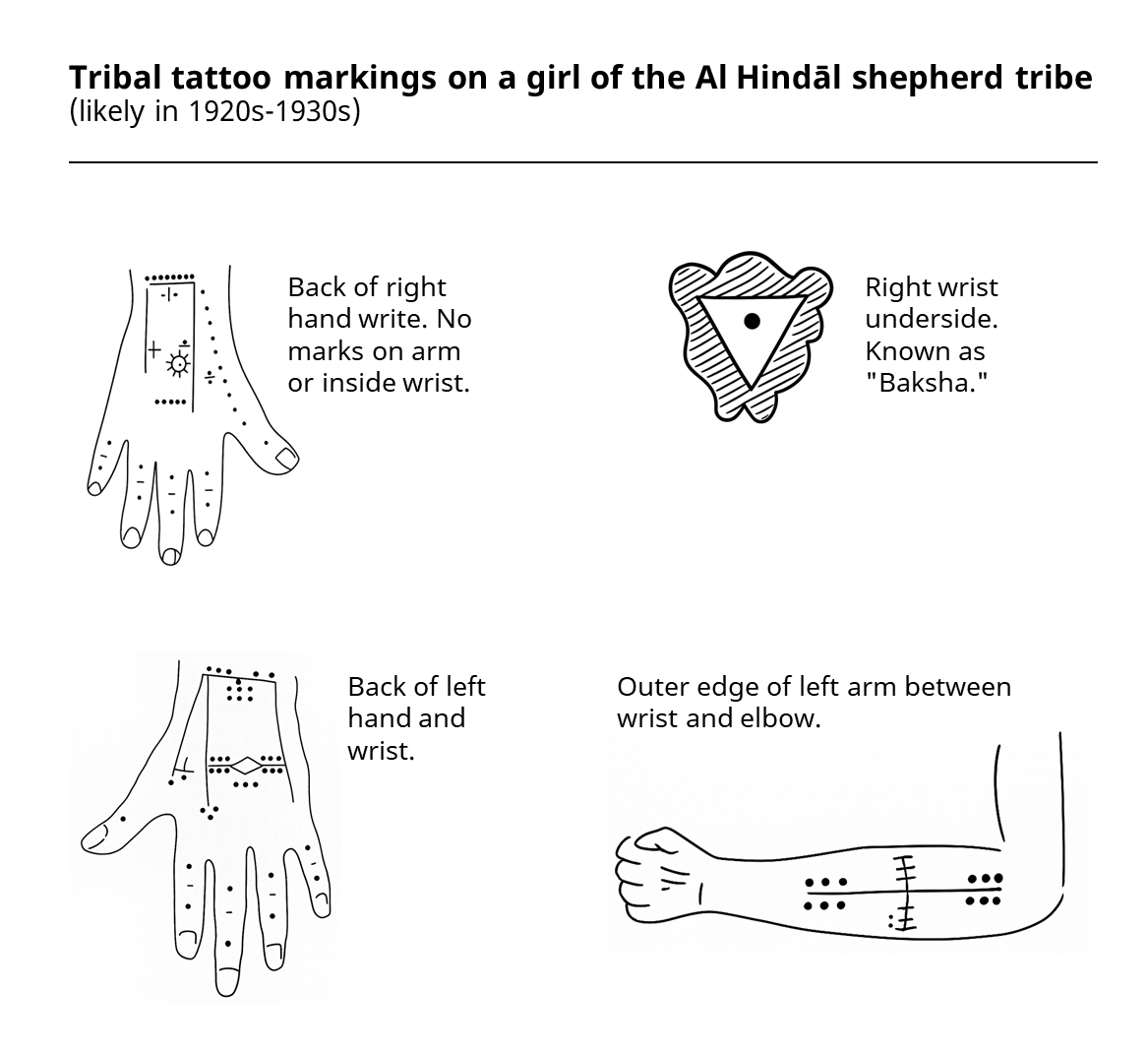

The book he left behind, published in 1956, is part memoir, part ethnography, and part political observation. It’s written with calm precision and deep respect for the people and places it documents. More than a historical account, it preserves fragments of a Kuwait that has all but vanished — from architecture and daily life to social rituals and customs (below is a sketch from the book showing the traditional tattoos of a Bedouin girl more than a century ago).

Illustration extracted from Kuwait and Her Neighbours — Chapter XIV.

A Prince in Exile

Midway through the book, Dickson introduces a name that made me pause: Abdulaziz Ibn Saud. At the time, he was a teenager living in exile in Kuwait.

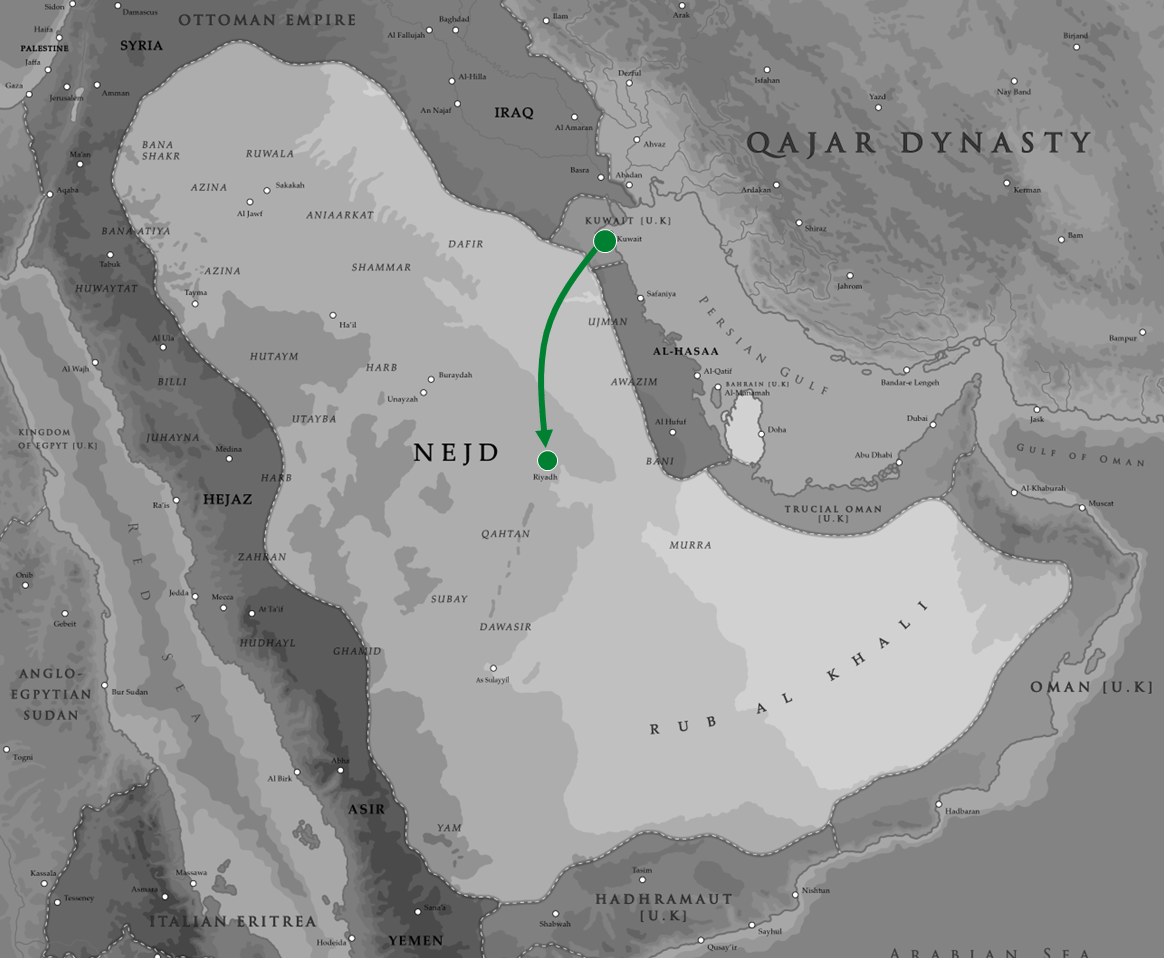

In 1891, the Al Saud family lost control of Riyadh after a long conflict with their rivals, the Al Rashid. Forced to leave their ancestral seat in Nejd, they crossed the desert and sought refuge in Kuwait. Sheikh Mubarak Al-Sabah, Kuwait’s ruler, welcomed them. Mubarak was navigating a volatile era of tribal conflict, Ottoman pressure, and growing British influence in the Gulf.

During this era, in 1899, Kuwait signed a secret treaty with the British. The agreement placed Kuwait under British protection in foreign affairs but preserved its internal autonomy. It gave Kuwait room to chart its own path while keeping larger powers at bay. While Mubarak built alliances and managed external pressures, Abdulaziz watched closely, assimilating the nuances of politics, leadership, and timing.

Watercolor illustration of Masmak Fort, where Abdulaziz seized Riyadh in 1902 — the first step toward founding Saudi Arabia.

The Return to Riyadh

In January 1902, at the age of 22, Abdulaziz left Kuwait with forty men: brothers, cousins, and loyal tribal fighters. Their goal was to retake Riyadh.

They travelled discreetly, evading Rashidi patrols, and camped for several days in the palm groves outside the city. According to Dickson, Abdulaziz had learned that the Rashidi governor, Ajlan, visited his wife each morning outside the fort.

On the third night, Abdulaziz and twenty-three of his men climbed onto the roof of that house and waited in silence. At dawn, as Ajlan crossed the courtyard, they struck. He ran toward the fort, but the gate was opened just in time for Abdulaziz’s men to follow him in.

“The story of ʿAbdul ʿAzīz’s seizure of the great fort in the centre of the town sounds almost like a fairy tale, and shows better than anything else the character of that extraordinary man. He discovered that ʿAjlān, the Rashīdī governor, had a wife whom he lodged in a house about fifty yards from the fort, and visited her for half an hour or so after morning prayers each day.

On the third night, ʿAbdul ʿAzīz quietly entered the lady’s house by way of the roof with twenty-three of his forty men and, having reassured the inmates, waited for dawn.

As expected, ʿAjlān emerged from the fort and crossed the open square. ʿAbdul ʿAzīz and his men rushed out. Ajlān ran back toward the fort, the wicket gate opened, and both pursuers and pursued dove inside. Moments later, the fort was under ʿAbdul ʿAzīz’s control.

With Riyādh secured, he called upon the garrison to surrender. They did, followed soon after by the townspeople. The news spread like wildfire throughout Najd, and all flocked to the Al Sa’ud standard.

The Start of a Nation

Riyadh was captured. Abdulaziz quickly fortified it. Rashidi forces returned days later but found the city too well defended and withdrew. Word of Riyadh’s recapture spread fast. Tribes rallied. Supporters returned. His father, Abdul Rahman, stepped aside and named his son the leader.

Abdulaziz Ibn Saud’s journey from Kuwait to Riyadh in 1902, across a map that shows how terrorities were divided in early 1900s.

From that small base in Riyadh, Abdulaziz spent the next three decades consolidating power, forging alliances, and expanding his influence. In 1932, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was declared. But its foundation was laid long before, in exile, beneath the stillness of Kuwait’s palm groves.

More Than a Century Later

This was a story I hadn’t heard before, which is exactly why I’ve been enjoying Dickson’s book. It’s full of moments he witnessed firsthand, the kind that rarely make it into textbooks but say so much about the region.

This particular story clearly helped shape the relationship between two nations over the past century. It’s one of those rare moments that quietly reveals the strength of regional ties. It speaks of two ruling families who stood by each other, and of two Gulf nations whose paths have been closely intertwined ever since.

More than anything, it’s a reminder that when a door is opened in a time of need, something lasting can take root. Acts of trust and support, even in exile, can forge bonds that endure across generations.

Over a hundred years later, the connection between Kuwait and Saudi Arabia still holds, built not just on shared interests, but on history, hospitality, and the quiet beginnings of something greater.

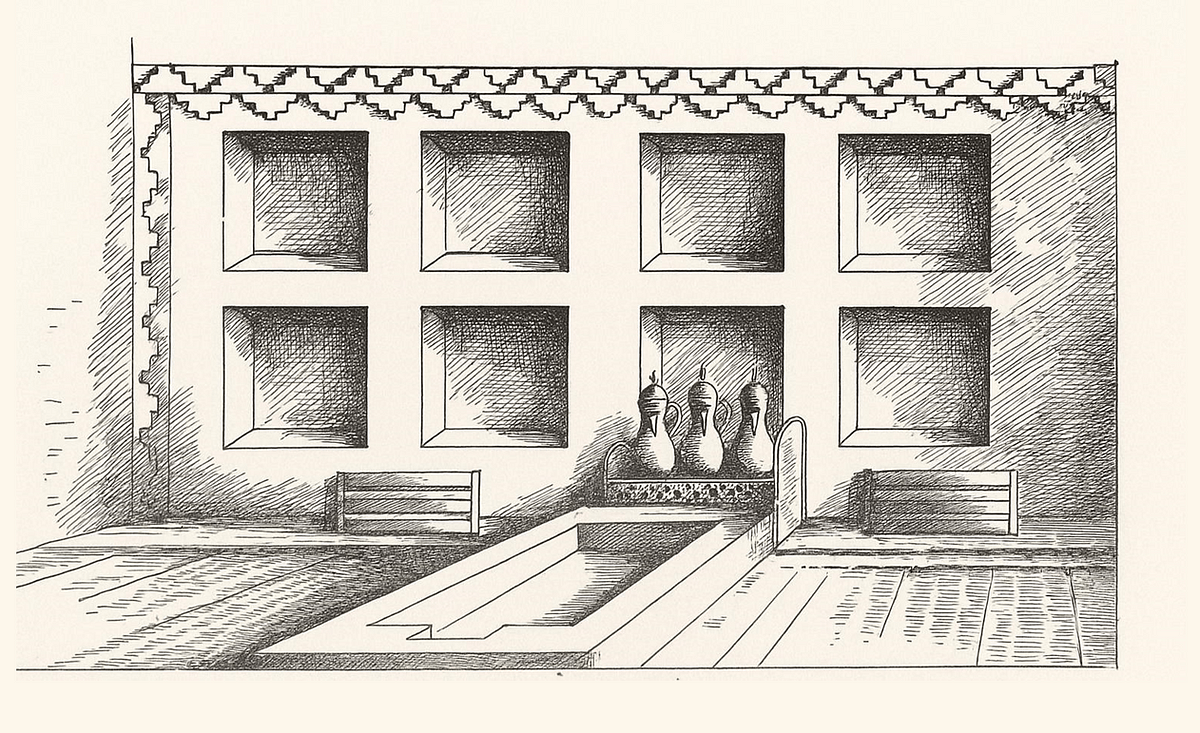

The coffee hearth in a Kuwaiti diwaniyah, where politics, alliances, and daily affairs were discussed. Illustration sketched in Dickson’s Kuwait and Her Neighbours, based on “Mirshid’s House” nearly a century ago.

Per My Last Thought…

I’ll keep reading Kuwait and Her Neighbours a few stories at a time. It’s not a book you read in one sitting, but one you return to, offering a portrait of the Gulf before oil, before borders, before nationhood. And as I go, if I will probably come across other interesting stories worth sharing, I’ll post it on PMLT, because some stories don’t just reveal the past, they quietly explain the present.